Every Wednesday at noon since 1992, demonstrators have gathered in front of the Japanese Embassy in Seoul, South Korea. These demonstrators demand justice for the crimes committed mainly during the Second World War. These crimes were inflicted on Korean women, often minors, known as "halmeoni", or comfort women. This term, a euphemism used by Japan, is hotly contested by Korean organizations demanding a formal apology and reparations from the Japanese government. They would also prefer the term "comfort women" (translated from the Japanese "慰安婦" - ianfu) to be replaced by "sex slaves".

What's the story behind the halmeoni?

By 1932, Korea had been annexed by Japan, and the conservative Japanese military regime was expanding into part of Asia. Under the pretext of preventing the rape of many Japanese women by Japanese soldiers during the war, but also to avoid the spread of numerous venereal diseases, numerous "comfort stations" were developed throughout colonial zones such as China. From 1937 onwards, the Imperial Japanese Army "recruited" young women in an extreme manner. Most of these women came from Korea and the poorest of Japan's colonial dominions. They were either lured by the promise of a better life in Japan, or simply kidnapped. From then on, they were taken to these "comfort stations", where they were raped several times a day to satisfy the Japanese soldiers. If they expressed an ounce of refusal, they were beaten.

Key dates

-Korea liberated but administered by the USA.

-Formation de l'Alliance des femmes fondatrices

The Foreign Affairs Committee and the US House ask Japan to acknowledge its involvement.

Comfort women were sex slaves from the late 1930s until 1945. The term "comfort women" is used by the perpetrator of this crime, Japan. The first comfort stations were set up in 1937 during the Sino-Japanese war, based on the same principle as those established since 1932 in China. These stations were supposed to limit the rapes caused by the Japanese military in the areas they conquered. A dozen or so women were grouped together in the nearly 2,000 (known) comfort stations spread across Asia and its islands. These houses had opening hours, and the women were given rest days during their menstruation and treatment for venereal diseases. They are subjected to sexual, physical and psychological violence. Their living conditions make a mockery of human rights.

These women were often single and underage. They were recruited for jobs as waitresses, cooks or to do laundry, which was all a lie. They came from countries controlled by the Japanese army: Korea, Burma, the Philippines, China, Indonesia and the Dutch East Indies. Sources estimate that between 179,000 and 220,000 women suffered these crimes. Very few of them were able to speak out against Japan's actions. At the end of the war, some victims were withdrawn from the rest of society.

In Korea, the last surviving comfort women live in comfort women's homes. There, they are cared for and protected. Almost seventy-eight years after the end of the war, Japan still does not recognize its crime. Many of these women have spoken out to denounce the acts they suffered and to make their story known.

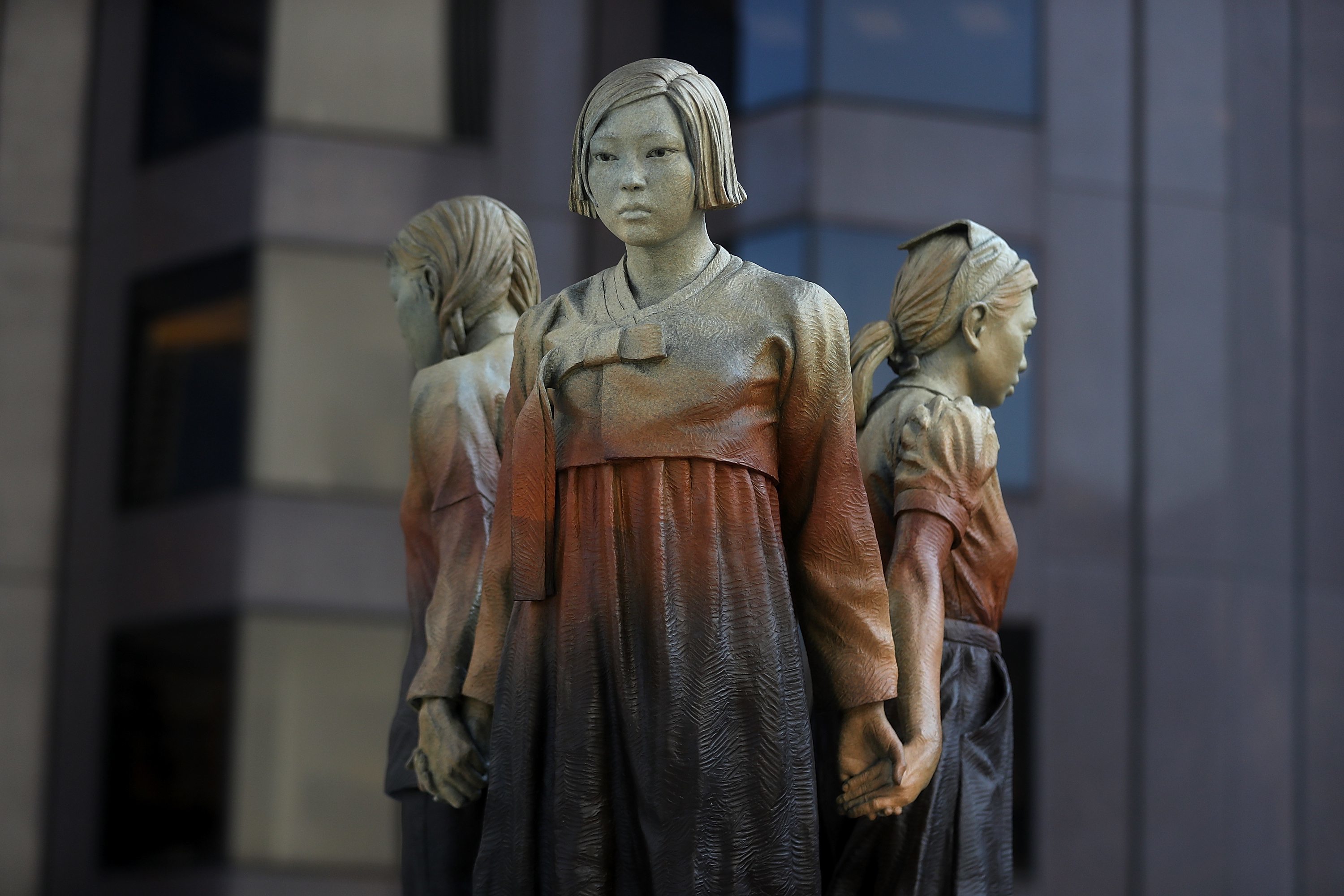

Since 1992, every Wednesday at noon, many Koreans have demonstrated at the foot of the Comfort Women statues to make their rights and memories heard. The first demonstration took place during the Japanese Prime Minister's visit to Korea, to no avail. The statues are located in major Korean cities in honor of the comfort women. One of these was placed opposite the Japanese consulate in Seoul. Its location strongly displeased the Japanese, who demanded its removal without much success. It remains there to this day.

In 2015, Japan proposed a deal to South Korea, including a sum of money in exchange and acknowledging its country's role in the crime. The comfort women refused the deal, seeing it as an attempt to buy their silence. Relations between the two powers have been fragile since the end of the 19th century and subsequent colonization. The crime against comfort women complicates relations between the two neighbors.

As the women affectionately known as halomni in Korea prepare to breathe their last, Japan has yet to acknowledge what it did to them. More than ever, the history of these women and their lives is being called into question.